My research examines the dynamics of surveillance and tactics of artistic resistance. I am considering artistic resistance to be the impenetrability of imagination, the subterfuge of irony, freedom of fantasy, and ambiguity of humour and metaphor.

The video work in the exhibition, Lines of Resistance, founded a research enquiry which spanned the control strategies of the death strip of former East Berlin, and contemporary experience of the Berlin Wall Memorial Site. In the context of Foucault’s writing on Bentham’s Panopticon the death strip operated as the ultimate control mechanism; exposure to those in positions of power, division and threat.1

The tour guide in the video speaks of the border space, and the material qualities and dynamics of the Stasi control tactics along the patrolled zone. He states that it was a crime to want to escape to the West, or to know that someone else wanted to escape, and discusses the desire of the Stasi to know everything. Tourists try to see more by peering through a gap in the wall’s construction behind which is the original patrolled zone, including remnants of the electric fences, the watchtower, paths, lights and sanded areas. I filmed some of this footage on an eight-foot high tripod with a remote control so that I could see over the wall. Another shot is taken from the viewing platform for tourists to enable a view from above of the whole site.

In the film other tour guides arrive and ask tourists ‘What can you see?’ and ‘What do you think you are going to see on the other side?’. Another guide discusses the fact that during the cold war he had never seen the wall from the Eastern side—he had never even seen a picture of the wall from the East. His cousin, in East Berlin, had never seen it either.

This work led to the production of high resolution panoramic photographs along the site of the original wall and death strip made with a GigaPan. The technology behind the GigaPan was developed by NASA with support from Google to take high definition panoramas of Mars.2 The image-stitching technology automatically combines hundreds or thousands of images taken with a digital camera into a single image. The resulting image has intense detail and forensic scientists now use this technology at crime scenes to uncover evidence which might not be apparent to the naked eye.

I took this image balanced on a makeshift tripod which I put together from wood which had been left over by the builders so that I could see over the wall into the building site behind it. As I took the image a man passed and told me that the building site was the new German Secret Service building.

This image spans the old and new materials of state surveillance. Both are in flux. On the left of the image are remnants of the patrolled zone: an abandoned military vehicle, and the scar of the now overgrown death strip. On the right of the image is the new German Federal Intelligence Service building, at the time the largest building site in Europe, now one of the world’s largest intelligence services.

Wikipedia details its now functioning activities as:

‘an early warning system, wiretapping and electronic surveillance of international communications, data collection of information on: terrorism, WMD, illegal transfer of technology, organized crime, weapons and drug trafficking, money laundering, illegal migration and information warfare’.3

This work stimulated research into camera positioning and point of view, on resolution, political resonance and temporality. It formed the basis of critical thinking around power and control, privacy and secrecy, visibility and invisibility, opacity and transparency.

This work was about seeing, having access to see the things that were hidden, about making what is, or was invisible, visible. The camera positioning explored points of view from the Stasi, from NASA, from those in East and West Berlin living through the Cold War, from tourists, and from myself.

The death strip panorama Chausse Strasse straddled the remnants of historical state-surveillance and the potential of the new. I was documenting a space originally managed by the former Ministry for State Security designed to deter and expose individuals attempting to escape to the West. I had positioned my camera to be able to see over the wall at a building which, when functioning, would have far reaching global access to information to support state control.

I am currently following the UK Government’s new Investigatory Powers Bill, also known as the Snoopers’ Charter, through Parliament. The most contentious part of the bill proposes to allow bulk collection of our personal information data and internet communication records, for example records of phone calls, our location and browsing history.

While visiting the Houses of Parliament, I entered spaces within which photography and documentation was forbidden inside a public chamber where MPs debated the most far reaching blanket surveillance of people within the UK.

The government guidance to visitors to Parliament states that:

The privacy of those who work or visit Parliament must always be respected. These rules are applicable to filming and photography on all devices including cameras, phones and tablet computers, and also extend to sound recording, painting and sketching. Tripods must not be used at any time.4

During the report stage of the parliamentary debate in the House of Commons, Conservative MP Sir Simon Burns (Chelmsford) said:

We cannot use an analogue approach to tackling criminals in a technical age, [...] The people outside Westminster who think this is about stopping people being rude on Twitter, or cleaning up the Facebook jungle, are wrong. The Bill is about protecting those rights—the right to be irreverent or to disagree; the right to surf the net without being at risk from those who would do us harm.5

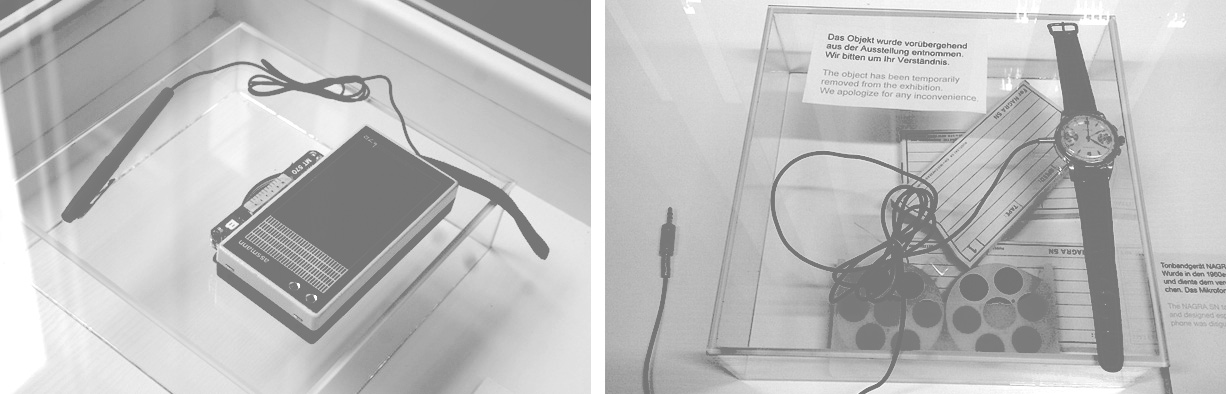

I thought this statement was funny with it’s clumsiness and obfuscation and was reminded of the analogue spyware I saw at the Stasi Museum used by the GDR’s Ministry of State Security during the Cold War. There were cameras housed in watering cans and within a wooden log, listening devices hidden inside a pen and cameras tucked within a 1970s tie or hidden behind a button. Clumsy and, although the fact that the former use of these devices was sinister, the simplicity and outdatedness had rendered them comical.

Over the past few months I have been taking my analogue equipment into Parliament and attempting to covertly document the Investigatory Powers Bill being debated. My early 1920s Ensign box camera now looks so basic and far removed from today’s cameras that it hardly looks like what we might consider a camera at all and it is also the same size as my sandwich box. I take most of my personal photographs on a Lomo film camera, which looks like a camera but also a bit like a toy camera. I have bought a Minox 1960s spy camera and a 1970s Realistic Dictaphone and have started to use my son Willem’s I Spy Ball. Children can set this device recording and roll it across the floor for thirty seconds of audio capture.

During the exhibition Testing Testing I will give a presentation detailing my account of my visits to the Houses of Parliament on 6 and 7 June 2016 and to the House of Lords on 29 June 2016.

...

1 In discussing Bentham’s Panopticon in relation to surveillance and control, Michel Foucault observes:

‘The arrangement of his room, opposite the central tower, imposes on him an axial visibility; but the divisions of the ring, those separated cells, imply a lateral invisibility. And this invisibility is the guarantee of order. [...] The crowd, a compact mass, a locus of multiple exchanges, individualities merging together, a collective effect is abolished and replaced by a collection of separated individualities.’ Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish (London: Penguin Books, 1991).

2 More information on GigaPan technology can be found at <http://gigapixelscience.gigapan.org/ > and <http://www.gigapan.com/gigapans/125210> [accessed 27 July 2016].

3 ‘Federal_Intelligence_Service’, Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Federal_Intelligence_Service_(Germany)> [accessed 27 July 2016].

4 Parliamentary guidelines for photography, filming and mobile phone use: <http://www.parliament.uk/visiting/access/photography-filming-and-mobile-phone-use/> [accessed 27 July 2016].

5 Conservative MP Sir Simon Burns (Chelmsford) speaking during the report stage of the parliamentary debate in the House of Commons 6 June 2016.