My research explores the use of scale models in self-organised practices, and as such is concerned with both the imaginative and physical activation of models.

One particular strand of my practice-led enquiry includes investigations into and speculations upon the nature of the model. What might the critical potential of distinct modes of model use be? For example, using an object as a surrogate for an absent entity, or the manipulation of materials to prototype a new idea. The life-span of the model offers multiple possibilities as the model shifts from a fluid to a more static state, and Teresa Stoppani has argued that the ‘re-activated’ model is a potent space for the creation of new knowledge.1 This is an area of particular interest in my practice, which draws upon the cultural associations and practical capacities of, for example, architects’ models, replicas, instructional models and enthusiast model making.

When Testing Testing invited us to undertake a dialogue with another researcher, I decided to extend an ongoing conversation with sound artist Rees Archibald. We share an interest in the role of intuition in making, in intimacy of scale, and things slightly below the usual threshold of attention: the barely audible or visible. These concerns manifest in our practices very differently, but our conversation about making has often seemed to suggest some shared ground.

Recently our discussion turned to the work of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, industrial engineers and management consultants who researched efficiency in labour during the early twentieth century. Their time and motion studies sought to capture and represent in isolation the single best way of doing any given task. This model (as exemplar) had the aim of advancing productivity by standardizing, removing idiosyncrasies in the act of making. This could be argued as editing the ‘conversation’ that might arise between a maker and their material, and indeed there was resistance to the Gilbreths’ challenge to the autonomy of the individual, yet the Gilbreths seemed to be looking precisely for the kind of skill we might associate with the craftsman. ‘The expert uses the motion model for learning the existing motion path and the possible lines for improvement. An efficient and skill-full motion has smoothness, grace, strong marks of habit, decision, lack of hesitation and is not fatiguing.’ 2

Their own research process, the production of the photographs, imagery and physical models, is also full of inventiveness and makerly skill and is somewhat seductive, so much so that the image of the work has been argued as being more successful than its application.3

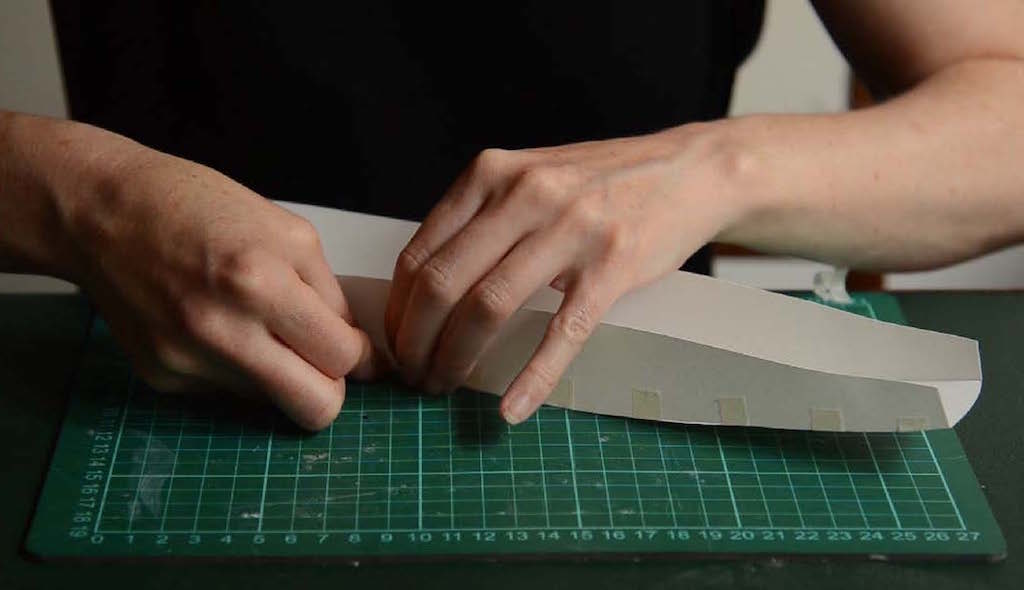

For Testing Testing, we decided to set up a parameter through which we could draw out something about making, close attention and emulation. The Gilbreths’ images were a point of departure. We reached the decision that we would each make a small paper model and record the sound of this process. We would then attempt to re-create the model made by the other, by listening closely to the audio, decoding and interpreting its construction. This would be done remotely, as we would be located in different countries at the time of production. Both the inefficiency of this undertaking (we are not skilled model-makers) and the curiosity at its root (to better understand what it is to experience an object at the stages of creation, apprehension, and translation using a method that would not be our default option) is in stark contrast to the Gilbreths’ aims. Play is an important component, and failure seems inevitable. But the attempt to learn through doing, and the close attention to some kind of trace left by the actions of another, connect our endeavour to their imagery and interest in the pursuit of skill, acknowledging the body in the process of making.

I’ve had a long standing preoccupation with the Gilbreths, and consider my work Pictorial House Modelling, After Miss Joyce Inall, 2015 as having a relationship to their imagery. In this work, I displayed a sequence of images from E.W. Hobb’s Pictorial House Modelling4 on a monitor, and mimicked as closely as possible the gestures depicted in the images used to demonstrate the stages of model production process. I used video to capture the reflections of these gestures in the screen on which the ‘slide show’ played.

In the performance, having no physical traction against an object, my hands tremble. Effort is discernible, but there is no physical product. The work might call to mind a magic trick, a tableux vivant, or a pseudoscientific instruction. In emulating the hand gestures, I did not learn how to achieve a pictorial model of a house, but my arms rehearsed and memorised the poses that made up the re-enactment of the model-making process depicted. The final work places us at several removes from the original process (making, poses to demonstrate making, photographs in book, digital images of those pages, performance reflected in the screen and recorded by video, projection of video) and is a reflection on the model as a site of nostalgia, memory, emulation, learning, of information and mis-information.

In The Craftsman, Richard Sennett describes the ‘Mirror Tool’, ‘an implement that invites us to think about ourselves.’ He also ponders the inadequacy of language as a ‘Mirror Tool’ for the physical movements of the human body. ‘One solution to the limits of language is to substitute the image for the word. The many plates, by many hands, that richly furnish the encyclopaedia made this assist for workers unable to explain themselves in words...’5

I understood the method I used in making Pictorial House Modelling, After Miss Joyce Inall, 2015 as a sort of ‘Mirror Tool’. Perhaps work in this exhibition will be an extension of that enquiry, but until it unfolds we will not know precisely what it will do.

I have recently been transcribing and closely analysing an interview I made with another friend about a model he had made. The slow, meticulous process of uncovering of the ‘fine grain’ of that interaction, through the act of transcription, felt to me as much like making as any studio work I have made. This seems significant when considering the development of this new work which contains a form of transcription and another dialogue between friends. Just prior to writing this text, I was sifting through the fragmentary notes that had accumulated in my studio over the last year. I came across a scrawled note; ‘Instead of documenting photographically, to play an object as a score— to imagine its sound…email Rees.’

It seems that the conversation had been waiting to happen.

...

1 Teresa Stoppani, The Model—Ian Kiaer: Tooth House talks series (CD) (Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, 2014).

2 Frank B. and Lillian M. Gilbreth, Applied motion study; a collection of papers on the efficient method to industrial preparedness, (New York: Sturgis and Walton Company, 1917) 127 <https://archive.org/ details/cu31924004621672> [accessed 16th May 2016].

3 Brian Price, Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and the manufacture and marketing of motion study, 1908-1924. Business and economic history (1989) 88-98.

4 Edward. W. Hobbs, Pictorial House Modelling (London, 1926). In the 1920s and 30s, the engineer Edward Walter Hobbs published a miscellany of instructional books, with subjects ranging from How to Make Model Clipper Ships to Concrete for Amateurs. The connecting principle appears to be the aim to develop skill in changing one’s environment, via the practice of this through domestic and even miniature scale. Edward. W. Hobbs, Pictorial House Modelling (London, 1926) employs carefully choreographed illustrations which demonstrate the stages of a process through the depiction of the maker’s hands, posed mid-action. A model for the making of models, his approach attempts to make an account of the tactile in the technical. ‘It is difficult to describe in words how to acquire the touch necessary to produce a really keen edge, but the knife should be worked to and fro over the stone, turning the wrist and thereby the blade of the knife at each end of the stroke…’ (Hobbs, 1926). In 1918 an engineer also named E. W. Hobbs patented a prosthetic hand.

5 Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (London: Penguin, 2009), p. 95.

Figure 1: Unknown photographer, From image verso: “2 cycles on drill press showing ‘HABIT’ positioning after transporting. Note the ‘hesitation’ before ‘grasping.’”, c. 1915, stereoscopic photograph, Frank B. Gilbreth Motion Study Photographs (1913–1917) Collection at the The Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University. The image has been cropped and the colour changed. Image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.